The-Art-of-Problem-Solving-in-Software-Engineering_How-to-Make-MySQL-Better

4.2 Data Structure

This section explores the fundamental data structures in MySQL, encompassing arrays, linked lists, queues, heaps, hash tables, red-black trees, B+ trees, and hybrid data structures. These data structures do not inherently possess advantages or disadvantages; their effectiveness depends on their application tailored to specific system architectures and the characteristics of practical data.

4.2.1 Array

An array consists of elements arranged in a specific order, typically of the same type. Elements are accessed via an integer index to specify the required item. Arrays are usually implemented with contiguous memory allocation and can be either fixed-length or resizable [45]. In MySQL, arrays commonly used include dynamic vectors and fixed-length arrays, with the choice depending on specific needs. Vectors can dynamically resize, while fixed-length arrays have a predetermined size.

In the MySQL InnoDB storage engine, MVCC ReadView uses a data structure similar to a vector to store the transaction IDs of all active transactions. This dynamic array supports varying lengths, adapting to changes in the active transaction list despite size fluctuations. For the Read Committed transaction isolation level, each read operation utilizes its own ReadView.

Here are some details about the ReadView object.

private:

// Disable copying

ReadView(const ReadView &);

ReadView &operator=(const ReadView &);

private:

/** The read should not see any transaction with trx id >= this

value. In other words, this is the "high water mark". */

trx_id_t m_low_limit_id;

/** The read should see all trx ids which are strictly

smaller (<) than this value. In other words, this is the

low water mark". */

trx_id_t m_up_limit_id;

/** trx id of creating transaction, set to TRX_ID_MAX for free

views. */

trx_id_t m_creator_trx_id;

/** Set of RW transactions that was active when this snapshot

was taken */

ids_t m_ids;

/** The view does not need to see the undo logs for transactions

whose transaction number is strictly smaller (<) than this value:

they can be removed in purge if not needed by other views */

trx_id_t m_low_limit_no;

The variable m_ids is a data structure of type ids_t, which closely resembles std::vector. For more details, see below:

/** This is similar to a std::vector but it is not a drop

in replacement. It is specific to ReadView. */

class ids_t {

typedef trx_ids_t::value_type;

/**

Constructor */

ids_t() : m_ptr(), m_size(), m_reserved() {}

/**

Destructor */

~ids_t() { ut::delete_arr(m_ptr); }

/** Try and increase the size of the array. Old elements are copied across.

It is a no-op if n is < current size.

@param n Make space for n elements */

void reserve(ulint n);

Do fixed-length arrays have practical value? In MySQL, buffer pool chunks are organized using fixed-length arrays. Details are provided below:

/** @brief The buffer pool structure.

NOTE! The definition appears here only for other modules of this

directory (buf) to see it. Do not use from outside! */

struct buf_pool_t {

...

/** Number of buffer pool chunks */

volatile ulint n_chunks;

/** New number of buffer pool chunks */

volatile ulint n_chunks_new;

/** buffer pool chunks */

buf_chunk_t *chunks;

/** old buffer pool chunks to be freed after resizing buffer pool */

buf_chunk_t *chunks_old;

/** Current pool size in pages */

ulint curr_size;

/** Previous pool size in pages */

ulint old_size;

/** Size in pages of the area which the read-ahead algorithms read

if invoked */

page_no_t read_ahead_area;

Above, the array name and type are defined, while below, dynamic memory allocation is carried out based on the array’s member type.

buf_pool->chunks = reinterpret_cast<buf_chunk_t *>(ut::zalloc_withkey(

UT_NEW_THIS_FILE_PSI_KEY, buf_pool->n_chunks * sizeof(*chunk)));

From a practical standpoint, leveraging fixed-length arrays can offer substantial performance benefits. Their stability prevents performance fluctuations due to memory reallocation, and their cache-friendliness further improves efficiency. Subsequent chapters will include several examples where the use of fixed-length arrays significantly improves performance or alleviates performance bottlenecks.

4.2.2 Linked List

A linked list (or simply “list”) is a linear collection of data elements, called nodes, where each node contains a value and a reference to the next node in the sequence. The primary advantage of linked lists over arrays is their efficiency in inserting and removing elements without relocating the entire list. However, operations like random access to a specific element are generally slower with linked lists compared to arrays [45].

MySQL commonly uses the list from the standard library, which typically implements a doubly linked list to facilitate easy insertion and deletion, though it often suffers from poor query performance. In mainstream NUMA architectures, linked lists are generally inefficient for querying due to non-contiguous memory access patterns. Consequently, linked lists are best suited as auxiliary data structures or for scenarios involving smaller data volumes.

In large-scale projects, to avoid the unpredictability of memory allocation in linked lists, a memory pool can be used for better management. Below is the list data structure used by undo. As the undo list grows longer, MVCC efficiency is significantly reduced.

using Recs = std::list<rec_t, mem_heap_allocator<rec_t>>;

...

/** Undo recs to purge */

Recs *recs;

4.2.3 Queue

In computer science, a queue is a collection of entities organized in a sequence, where entities can be added at one end and removed from the other. The operation of adding an element to the rear is called enqueue, while removing an element from the front is called dequeue. This makes a queue a first-in-first-out (FIFO) data structure, meaning the first element added will be the first one removed. In other words, elements are processed in the order they are added.

Queues are linear data structures, or sequential collections, and are commonly used in computer programs. They can be implemented using circular buffers or linked lists. In MySQL, queues are often encapsulated with additional functionalities, such as synchronized queues and double-ended queues, for FIFO processing needs. For instance, the incoming member shown below uses a synchronized queue to store Group Replication’s applier packets, serving as a cache for data related to Paxos network interactions and relay log disk writes. This buffering helps manage data when relay log writing lags behind.

/* The incoming event queue */

Synchronized_queue<Packet *> *incoming;

Double-ended queues are commonly used in various applications. For instance, MySQL utilizes std::deque to implement a general-purpose mem_root_deque. Details are provided below:

/**

A (partial) implementation of std::deque allocating its blocks on a MEM_ROOT.

This class works pretty much like an std::deque with a Mem_root_allocator,

and used to be a forwarder to it. However, libstdc++ has a very complicated

implementation of std::deque, leading to code blowup (e.g., operator[] is

23 instructions on x86-64, including two branches), and we cannot easily use

libc++ on all platforms. This version is instead:

- Optimized for small, straight-through machine code (few and simple

instructions, few branches).

- Optimized for few elements; in particular, zero elements is an important

special case, much more so than 10,000.

...

*/

template <class Element_type>

class mem_root_deque {

4.2.4 Heap

In computer science, a heap is a tree-based data structure that maintains the heap property and is typically implemented using an array [45]. It serves as an efficient implementation of the abstract data type known as a priority queue. Priority queues are often referred to as “heaps” regardless of their underlying implementation. In a heap, the element with the highest (or lowest) priority is always at the root. However, unlike a sorted structure, a heap is partially ordered.

Heaps are particularly useful when there is a need to repeatedly access and remove the element with the highest or lowest priority, or when insertions and removals of the root node occur frequently. Priority queues, which are frequently implemented with heaps, are also used in MySQL. For instance, in MySQL 8.0.34, the data structure purge_pg_t (detailed below) utilizes the priority_queue from the standard library to efficiently find the oldest transaction ID.

typedef std::priority_queue<

TrxUndoRsegs, std::vector<TrxUndoRsegs, ut::allocator<TrxUndoRsegs>>,

TrxUndoRsegs>

purge_pq_t;

From a mathematical perspective, heap data structures have a balanced tree structure with minimal theoretical tree levels. However, in modern architectures, they present notable drawbacks. Heaps have a non-sequential access pattern, moving from the root to the leaves, which is not cache-friendly. This makes heaps suitable for relatively small datasets but less efficient as data scales up. Inefficient cache access may explain why heap-based algorithms, like heap sort, don’t outperform quicksort in average performance, despite their theoretical advantages.

4.2.5 Hash Table

A hash table, also known as a hash map, is a data structure designed for fast value retrieval based on keys. It uses a hashing function to map keys to indices in an array, allowing for average constant-time access. Hash tables are commonly used in dictionaries, caches, and database indexing. Despite their efficiency, hash collisions can degrade performance, and techniques such as chaining and open addressing are used to manage them.

The primary advantage of traditional hash tables lies in their fast query speed. However, due to the scattered memory pointers stored in hash slots, they may not be very cache-friendly. This scattering can lead to reduced efficiency during frequent access operations. To address this issue, solutions like Google’s Swiss Table have emerged, which employ a cache-friendly and more efficient approach to make comparisons and insertions faster. However, such solutions are not universal and are not particularly suitable for database usage.

In MySQL, hash tables are widely used, leveraging both STL types like unordered_set and unordered_map, as well as custom-designed hash tables tailored to specific use cases. For instance, the hash_table_t data type, used in the buffer pool for page management, exemplifies such specialized implementations.

/** Hash table of buf_page_t or buf_block_t file pages, buf_page_in_file() ==

true, indexed by (space_id, offset). page_hash is protected by an array of

mutexes. */

hash_table_t *page_hash;

The data members of hash_table_t are as follows:

/* The hash table structure */

class hash_table_t {

public:

hash_table_t(size_t n) {

const auto prime = ut::find_prime(n);

cells = ut::make_unique<hash_cell_t[]>(prime);

set_n_cells(prime);

/* Initialize the cell array */

hash_table_clear(this);

}

~hash_table_t() { ut_ad(magic_n == HASH_TABLE_MAGIC_N); }

/** Returns number of cells in cells[] array.

If type==HASH_TABLE_SYNC_RW_LOCK it can be used:

- without any latches to peek a value, before hash_lock_[sx]_confirm

- when holding S-latch for at least one n_sync_obj to get the "real" value

@return value of n_cells

*/

size_t get_n_cells() { return n_cells.load(std::memory_order_relaxed); }

/** Returns a helper class for calculating fast modulo n_cells.

If type==HASH_TABLE_SYNC_RW_LOCK it can be used:

- without any latches to peek a value, before hash_lock_[sx]_confirm

- when holding S-latch for at least one n_sync_obj to get the "real" value */

const ut::fast_modulo_t get_n_cells_fast_modulo() {

return n_cells_fast_modulo.load();

}

...

Note that the page-based buffer pool has low caching efficiency, and the page translation table is a scalability bottleneck [64].

The certification database of Group Replication uses the std::unordered_map hash table to handle a large volume of certification information.

typedef std::unordered_map<

std::string, Gtid_set_ref *, std::hash<std::string>,

std::equal_to<std::string>,

Malloc_allocator<std::pair<const std::string, Gtid_set_ref *>>>

Certification_info;

...

/**

Certification database.

*/

Certification_info certification_info;

Despite utilizing efficient data structures like hash tables, the certification database faces performance challenges due to frequent access to elements. This problem arises because the memory access pattern in the certification database is non-contiguous, leading to inefficient memory access. Consequently, while hash tables offer advantages, they are not always the optimal choice for performance in this context.

4.2.6 Red-Black Tree

In computer science, a red-black tree is a self-balancing binary search tree known for efficient storage and retrieval of ordered data. Each node in a red-black tree has an additional “color” bit, typically red or black, which helps maintain the tree’s balanced structure. MySQL frequently uses the map from the STL (Standard Template Library), which implements a red-black tree to preserve order. In contrast, unordered_map in the STL is a hash table and does not maintain order, which is why it is called an “unordered map”.

The Pages below illustrates the use of a map data structure for efficient lookup, modification, and sequential traversal.

/* Assuming a page size, read the space_id from each page and store it

in a map. Find out which space_id is agreed on by majority of the

pages. Choose that space_id. */

for (uint32_t page_size = UNIV_ZIP_SIZE_MIN; page_size <= UNIV_PAGE_SIZE_MAX;

page_size <<= 1) {

/* map[space_id] = count of pages */

typedef std::map<space_id_t, ulint, std::less<space_id_t>,

ut::allocator<std::pair<const space_id_t, ulint>>>

Pages;

Pages verify;

ulint page_count = 64;

ulint valid_pages = 0;

/* Adjust the number of pages to analyze based on file size */

while ((page_count * page_size) > file_size) {

--page_count;

}

MySQL has also implemented a red-black tree tailored to its specific needs. For instance, the code snippet below shows SEL_ROOT, a red-black tree utilized to store key ranges.

/**

A graph of (possible multiple) key ranges, represented as a red-black

binary tree. There are three types (see the Type enum); if KEY_RANGE,

we have zero or more SEL_ARGs, described in the documentation on SEL_ARG.

As a special case, a nullptr SEL_ROOT means a range that is always true.

This is true both for keys[] and next_key_part.

*/

class SEL_ROOT {

...

/**

Insert the given node into the tree, and update the root.

@param key The node to insert.

*/

void insert(SEL_ARG *key);

/**

Delete the given node from the tree, and update the root.

@param key The node to delete. Must exist in the tree.

*/

void tree_delete(SEL_ARG *key);

/**

Find best key with min <= given key.

Because of the call context, this should never return nullptr to get_range.

@param key The key to search for.

*/

SEL_ARG *find_range(const SEL_ARG *key) const;

...

Generally, red-black trees offer advantages such as low insertion and update costs and support for sequential traversal. However, their non-sequential memory access can reduce cache efficiency, making them less ideal for high-performance, compute-intensive tasks.

4.2.7 B+ Tree

A B+ tree is an m-ary tree characterized by a large number of children per node, including a root, internal nodes, and leaves. The root may either be a leaf or a node with two or more children [45].

B+ trees excel in block-oriented storage contexts, such as filesystems, due to their high fanout (typically around 100 or more pointers per node). This high fanout reduces the number of I/O operations needed to locate an element, making B+ trees especially efficient when data cannot fit into memory and must be read from disk.

Concurrency control of operations in B-trees, however, is perceived as a difficult subject with many subtleties and special cases [70]. For details on this subject, please refer to the paper “A Survey of B-Tree Locking Techniques”.

InnoDB employs B+ trees for its indexing, leveraging their ability to ensure a fixed maximum number of reads based on the tree’s depth, which scales efficiently. For specific details on B+ tree implementation in MySQL, refer to the file btr/btr0btr.cc.

4.2.8 Hybrid Data Structure

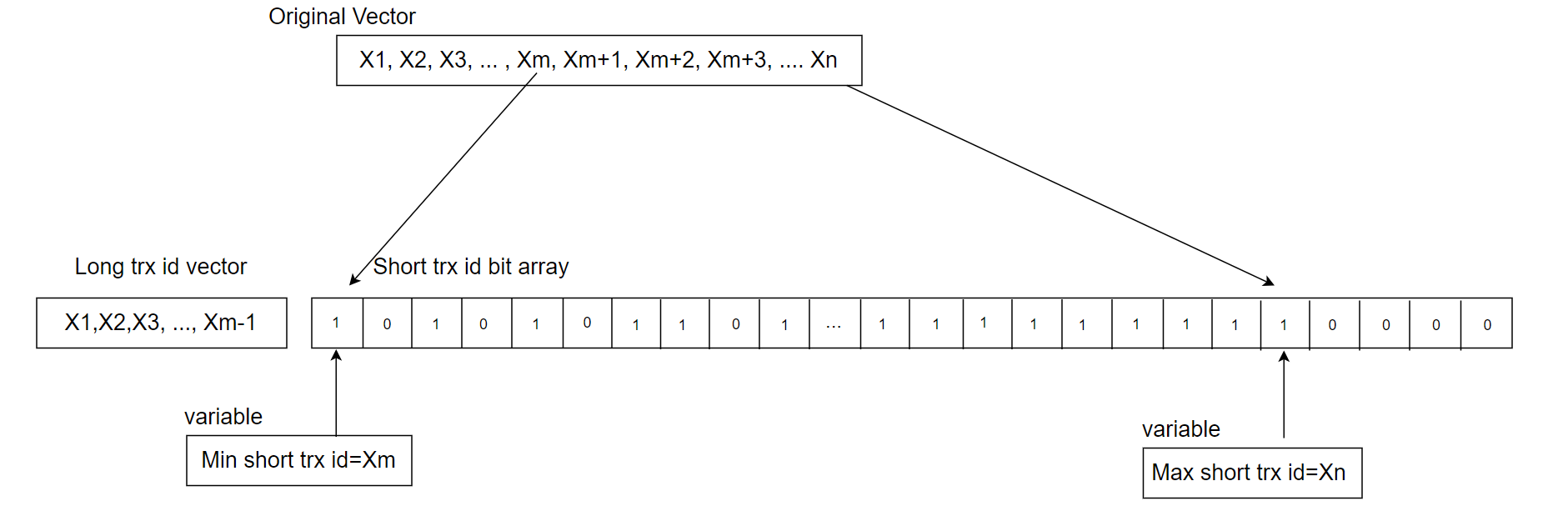

In various application scenarios, relying on a single data structure may not always yield optimal performance. Combining different data structures can often lead to significant improvements. For instance, in MySQL, the MVCC ReadView initially uses a dynamic array (vector) to maintain the active transaction list, utilizing binary search for querying. However, in high-concurrency environments, this list can grow excessively, making it less efficient in NUMA environments. To mitigate this problem, a hybrid approach is employed: recent transactions are stored in a static array for quick access, while long-running transactions are placed in a dynamic array. This dual-array strategy, managed by multiple variables, improves access speed and efficiency. For further details, see below:

Figure 4-8. A new hybrid data structure suitable for active transaction list in MVCC ReadView.

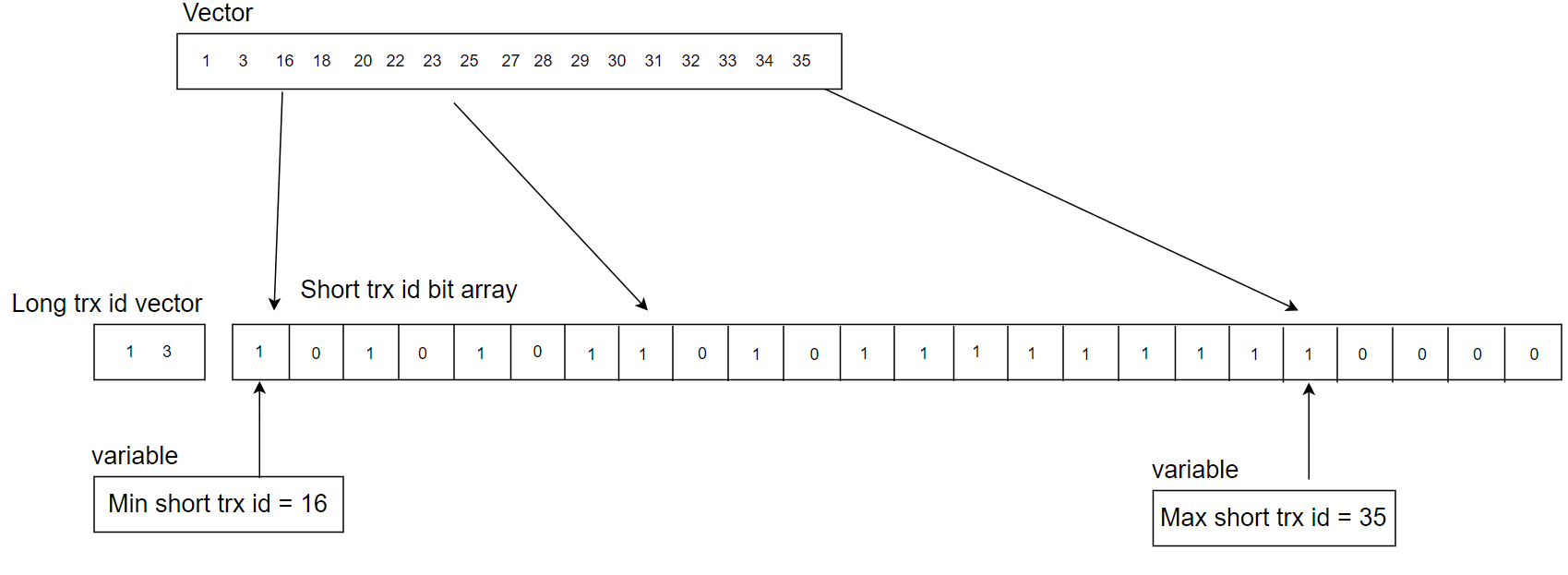

To better illustrate the concept of hybrid data structures, consider the following example:

Figure 4-9. A detailed example for the new hybrid data structure for active transaction list.

The active transaction list length is 17, with each transaction ID requiring 8 bytes. Storing this using a dynamic array (vector) would necessitate at least 17 * 8 = 136 bytes. By switching to a hybrid data structure, most transaction IDs are stored in a static array using a 3-byte bit representation, while a dynamic array holds two transaction IDs (1 and 3), occupying 16 bytes. Additionally, two auxiliary variables consume 16 bytes. Consequently, the hybrid data structure totals 3 + 16 + 16 = 35 bytes, which is 101 bytes less than the original approach.

Regarding query efficiency, the hybrid data structure offers substantial improvements. For instance, to check if transaction ID=24 is in the active transaction list:

- In the original approach, a binary search is needed, with a time complexity of O(log n).

- With the hybrid structure, using the minimum short transaction ID as a baseline allows direct querying through the static data, achieving a time complexity of O(1).

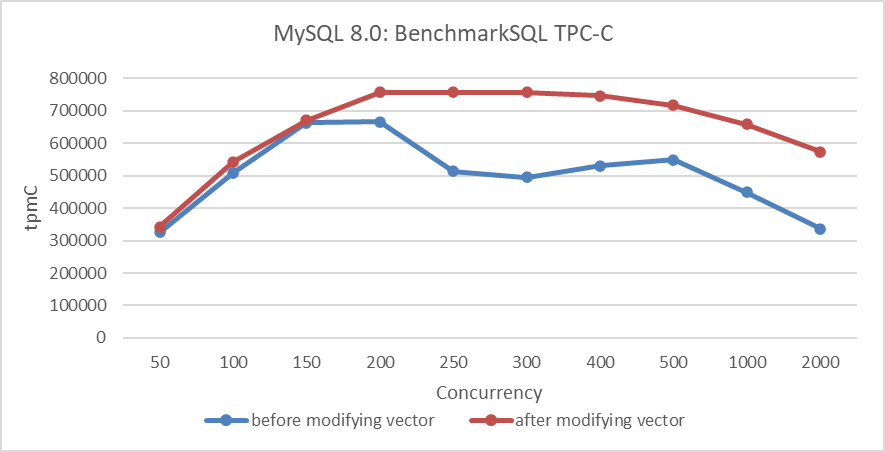

In NUMA environments, as shown in the figure below, it can be seen that simply changing the data structure can significantly increase the throughput of TPC-C under high-concurrency conditions, greatly alleviating scalability problems related to MVCC ReadView.

Figure 4-10. Performance improvement with new hybrid data structure in NUMA.