The-Art-of-Problem-Solving-in-Software-Engineering_How-to-Make-MySQL-Better

4.3 Algorithm

This section covers various problem-solving algorithms in MySQL, including search algorithms, sorting algorithms, greedy algorithms, dynamic programming, amortized analysis, and the Paxos series of algorithms.

4.3.1 Search Algorithm

In computer science, a search algorithm is designed to locate information within a specific data structure or search space [45].

MySQL commonly employs several search algorithms, including binary search, red-black tree search, B+ tree search, and hash search. Binary search is effective for searching datasets without special characteristics or when dealing with smaller datasets. For instance, binary search is used to determine if a record is visible in the active transaction list, as detailed below:

/** Check whether the changes by id are visible.

@param[in] id transaction id to check against the view

@param[in] name table name

@return whether the view sees the modifications of id. */

[[nodiscard]] bool changes_visible(trx_id_t id,

const table_name_t &name) const {

ut_ad(id > 0);

if (id < m_up_limit_id || id == m_creator_trx_id) {

return (true);

}

check_trx_id_sanity(id, name);

if (id >= m_low_limit_id) {

return (false);

} else if (m_ids.empty()) {

return (true);

}

const ids_t::value_type *p = m_ids.data();

return (!std::binary_search(p, p + m_ids.size(), id));

}

The B+ tree search, implemented in btr/btr0btr.cc, is a well-established method ideal for indexing scenarios. Hash lookup, another prevalent search method in MySQL, is frequently used, such as in Group Replication for certification databases, as detailed below:

bool Certifier::add_item(const char *item, Gtid_set_ref *snapshot_version,

int64 *item_previous_sequence_number) {

DBUG_TRACE;

mysql_mutex_assert_owner(&LOCK_certification_info);

bool error = true;

std::string key(item);

Certification_info::iterator it = certification_info.find(key);

snapshot_version->link();

if (it == certification_info.end()) {

std::pair<Certification_info::iterator, bool> ret =

certification_info.insert(

std::pair<std::string, Gtid_set_ref *>(key, snapshot_version));

error = !ret.second;

} else {

*item_previous_sequence_number =

it->second->get_parallel_applier_sequence_number();

if (it->second->unlink() == 0) delete it->second;

it->second = snapshot_version;

error = false;

}

...

return error;

}

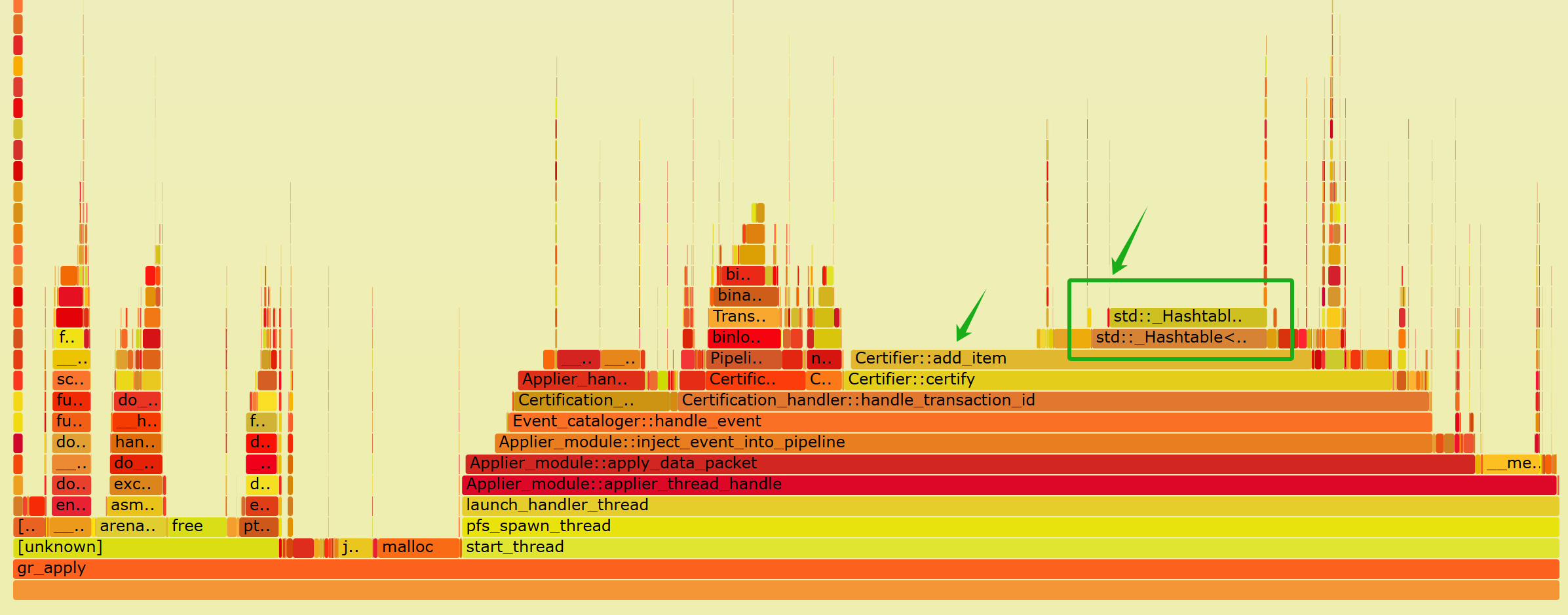

The choice of search algorithm is flexible and usually adjusted based on performance bottlenecks. For example, the hash-based search algorithm mentioned earlier became the primary bottleneck in the Group Replication applier thread operations, as illustrated by the specific performance flame graph below:

Figure 4-11. An example of bottlenecks in hash-based search algorithm.

The figure shows that hash search in Certify::add_item accounts for half of the total time, highlighting a significant bottleneck. This suggests the need to explore alternative search algorithms. Further details on potential solutions are discussed in the following chapters.

4.3.2 Sorting Algorithm

In computer science, a sorting algorithm arranges elements of a list into a specific order, with the most frequently used orders being numerical and lexicographical, either ascending or descending. Efficient sorting is crucial for optimizing the performance of other algorithms, such as search and merge algorithms, which require sorted input data [45].

Commonly used sorting algorithms do not inherently have a distinction of superiority or inferiority; each serves its own purpose. For example, consider std::sort from the C++ Standard Library. It employs different sorting algorithms based on the data’s characteristics. When the data is mostly ordered, it uses insertion sort. See details below:

// sort

template <typename _RandomAccessIterator, typename _Compare>

_GLIBCXX20_CONSTEXPR inline void __sort(_RandomAccessIterator __first,

_RandomAccessIterator __last,

_Compare __comp) {

if (__first != __last) {

std::__introsort_loop(__first, __last, std::__lg(__last - __first) * 2,

__comp);

std::__final_insertion_sort(__first, __last, __comp);

}

}

Insertion sort is used in cases where the data is mostly ordered because it has a time complexity close to linear in such scenarios. More importantly, insertion sort accesses data sequentially, which significantly improves cache efficiency. This cache-friendly nature makes insertion sort highly suitable for sorting small amounts of data.

For instance, in the std::sort function, when calling the __introsort_loop function, if the number of elements is less than or equal to 16, sorting is skipped, and control returns to the sort function. The sort function then utilizes insertion sort for sorting.

/**

* @doctodo

* This controls some aspect of the sort routines.

*/

enum { _S_threshold = 16 };

/// This is a helper function for the sort routine.

template <typename _RandomAccessIterator, typename _Size, typename _Compare>

_GLIBCXX20_CONSTEXPR void __introsort_loop(_RandomAccessIterator __first,

_RandomAccessIterator __last,

_Size __depth_limit,

_Compare __comp) {

while (__last - __first > int(_S_threshold)) {

if (__depth_limit == 0) {

std::__partial_sort(__first, __last, __last, __comp);

return;

}

--__depth_limit;

_RandomAccessIterator __cut =

std::__unguarded_partition_pivot(__first, __last, __comp);

std::__introsort_loop(__cut, __last, __depth_limit, __comp);

__last = __cut;

}

}

Within the __introsort_loop function, if the recursion depth exceeds a threshold, the partial_sort function, which is based on heap data structures and offers stable performance, is utilized. Overall, the main part of __introsort_loop employs an improved version of quicksort, eliminating left recursion and reducing the overhead of function calls.

Discussing sorting algorithms is essential not only because MySQL extensively uses these standard library sort algorithms but also to draw insights on optimization strategies from their implementations. This involves selecting different algorithms based on specific circumstances to leverage their respective strengths, thereby improving the overall performance of the algorithm.

In MySQL code, similar optimization principles are applied. For instance, in the sort_buffer function, when the key_len value is small, it uses the Mem_compare function, which is suitable for short keys. When prefilter_nth_element > 0, it employs nth_element (similar to the partitioning idea of quicksort), selecting the required elements for subsequent sorting.

size_t Filesort_buffer::sort_buffer(Sort_param *param, size_t num_input_rows,

size_t max_output_rows) {

...

if (num_input_rows <= 100) {

if (key_len < 10) {

param->m_sort_algorithm = Sort_param::FILESORT_ALG_STD_SORT;

if (prefilter_nth_element) {

nth_element(it_begin, it_begin + max_output_rows - 1, it_end,

Mem_compare(key_len));

it_end = it_begin + max_output_rows;

}

sort(it_begin, it_end, Mem_compare(key_len));

...

return std::min(num_input_rows, max_output_rows);

}

param->m_sort_algorithm = Sort_param::FILESORT_ALG_STD_SORT;

if (prefilter_nth_element) {

nth_element(it_begin, it_begin + max_output_rows - 1, it_end,

Mem_compare_longkey(key_len));

it_end = it_begin + max_output_rows;

}

sort(it_begin, it_end, Mem_compare_longkey(key_len));

...

return std::min(num_input_rows, max_output_rows);

}

param->m_sort_algorithm = Sort_param::FILESORT_ALG_STD_STABLE;

// Heuristics here: avoid function overhead call for short keys.

if (key_len < 10) {

if (prefilter_nth_element) {

nth_element(it_begin, it_begin + max_output_rows - 1, it_end,

Mem_compare(key_len));

it_end = it_begin + max_output_rows;

}

stable_sort(it_begin, it_end, Mem_compare(key_len));

...

} else {

...

}

return std::min(num_input_rows, max_output_rows);

}

In general, when using sorting algorithms, the key principles are flexibility in application and cache-friendliness. By considering the algorithm’s complexity, one can find the most suitable sorting algorithm.

4.3.3 Greedy Algorithm

A greedy algorithm follows the heuristic of making the locally optimal choice at each stage. Although it often does not produce an optimal solution for many problems, it can yield locally optimal solutions that approximate a globally optimal solution within a reasonable amount of time.

One of the most challenging problems in generating an execution plan based on SQL is selecting the join order. Currently, MySQL’s execution plan uses a straightforward greedy algorithm for join order, which performs well in certain scenarios. See the details below for more information:

/**

Find a good, possibly optimal, query execution plan (QEP) by a greedy search.

...

@note

The following pseudocode describes the algorithm of 'greedy_search':

@code

procedure greedy_search

input: remaining_tables

output: pplan;

{

pplan = <>;

do {

(t, a) = best_extension(pplan, remaining_tables);

pplan = concat(pplan, (t, a));

remaining_tables = remaining_tables - t;

} while (remaining_tables != {})

return pplan;

}

...

*/

bool Optimize_table_order::greedy_search(table_map remaining_tables) {

Determining the optimal join order is an NP-hard problem, making it prohibitively costly in terms of computational resources for complex joins. Consequently, MySQL uses a greedy algorithm. Although this approach may not always yield the absolute best join order, it balances computational efficiency with decent overall performance.

In some join operations, the greedy algorithm’s join order selection can result in poor performance, which may explain why users occasionally criticize MySQL’s performance.

4.3.4 Dynamic Programming

Dynamic programming simplifies a complex problem by breaking it down into simpler sub-problems recursively. A problem exhibits optimal substructure if it can be solved optimally by solving its sub-problems and combining their solutions. Additionally, if sub-problems are nested within larger problems and dynamic programming methods are applicable, there is a relationship between the larger problem’s value and the sub-problems’ values. Two key attributes for applying dynamic programming are optimal substructure and overlapping sub-problems [45].

In the context of execution plan optimization, MySQL 8.0 has explored using dynamic programming algorithms to determine the optimal join order. This approach can greatly improve the performance of complex joins, though it remains experimental in its current implementation.

It is important to note that, due to potentially inaccurate cost estimation, the join order determined by dynamic programming algorithms may not always be the true optimal solution. Dynamic programming algorithms often provide the best plan but can have high computational overhead and may suffer from large costs due to incorrect cost estimation [55]. For a deeper understanding of the complex mechanisms involved, readers can refer to the paper “Dynamic Programming Strikes Back” [35].

4.3.5 Amortized Analysis

In computer science, amortized analysis is a method for analyzing an algorithm’s complexity, specifically how much of a resource, such as time or memory, it takes to execute. The motivation for amortized analysis is that considering the worst-case runtime can be overly pessimistic. Instead, amortized analysis averages the running times of operations over a sequence [45].

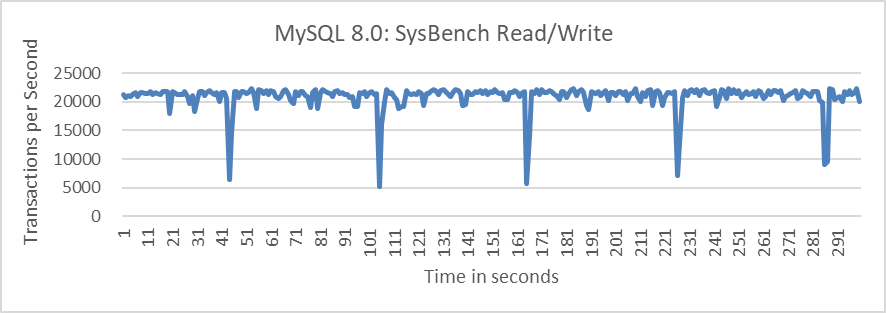

This section discusses applying amortized analysis to address MySQL problems. While it differs from traditional amortized analysis, the underlying principles are similar and find many practical applications in addressing MySQL performance problems. For example, during the refactoring of Group Replication, significant jitter was observed when cleaning up outdated certification database information in multi-primary scenarios. The figure below shows read-write tests in MySQL’s multi-primary mode with Group Replication, using SysBench at 100 concurrency levels over 300 seconds.

Figure 4-12. Performance fluctuation in MySQL Group Replication.

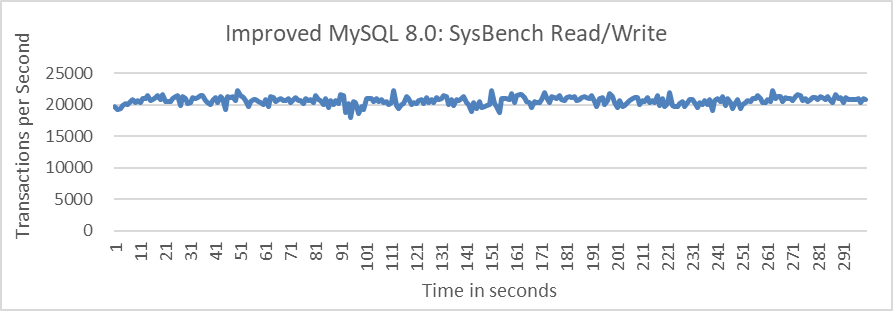

To address this problem, an amortization strategy was adopted for cleaning up outdated certification database information. See the specific details in the following figure:

Figure 4-13. Eliminated performance fluctuations in enhanced MySQL Group Replication.

MySQL experienced severe performance fluctuations primarily due to cleaning outdated certification database information every 60 seconds. After redesigning the strategy to clean every 0.2 seconds, resulting in performance fluctuations on the order of milliseconds (ms), these fluctuations became imperceptible during testing. The improved version of MySQL has eliminated sudden performance drops, mainly by applying the amortized approach to reduce significant fluctuations.

It is important to note that cleaning every 0.2 seconds requires each MySQL node to promptly send its GTID information at intervals of approximately 0.2 seconds. This high-frequency sending is challenging to meet using traditional Multi-Paxos algorithms because these algorithms typically require leader stability over a period of time. Therefore, a single-leader based Multi-Paxos algorithm struggles to handle sudden performance drops effectively, as the underlying algorithm lacks support for such frequent operations.

4.3.6 Paxos

Maintaining consistency among replicas in the face of arbitrary failures has been a major focus in distributed systems for several decades. While naive solutions may work for simple cases, they often fail to provide a general solution. Paxos is a family of protocols designed to achieve consensus among unreliable or fallible processors. Consensus involves agreeing on a single result among multiple participants, a task that becomes challenging when failures or communication problems arise. The Paxos family is widely regarded as the only proven solution for achieving consensus with three or more replicas, as it addresses the general problem of reaching agreement among 2F + 1 replicas while tolerating up to F failures. This makes Paxos a fundamental component of State Machine Replication (SMR) and one of the simplest algorithms for ensuring high availability in clustered environments [26].

The mathematical foundation of Paxos is rooted in set theory, specifically the principle that the intersection of a majority of sets must be non-empty. This principle is key to solving high availability problems in complex scenarios.

However, the pure Paxos protocol often falls short in meeting practical business needs, particularly in environments with significant network latency. To address this, various strategies and enhancements have been developed, leading to several Paxos variants, such as Multi-Paxos, Raft, and Mencius in Group Replication. The following figure illustrates an idealized sequence of Multi-Paxos, where a stable leader allows a proposal message to achieve consensus and return a result to the user within a single Round-trip Time (RTT) [45].

Client Servers

X-------->| | | Request

| X->|->| Accept!(N,I+1,W)

| X<>X<>X Accepted(N,I+1)

|<--------X | | Response

| | | |

Starting with MySQL 8.0.27, Group Replication incorporates two Paxos variant algorithms: Mencius and the traditional Multi-Paxos. Mencius was designed to address the challenge of multiple leaders in Paxos and was initially developed for wide-area network applications. It allows each node to directly send propose messages, enabling any MySQL secondary to communicate with the cluster at any time without burdening a single Paxos leader. This approach supports consistency in reads and writes and improves the multi-primary functionality of Group Replication. In contrast, the Multi-Paxos algorithm employs a single-leader approach. Non-leader nodes must request a sequence number from the leader before sending messages to the cluster. Frequent requests to the leader can create a bottleneck, potentially limiting performance.

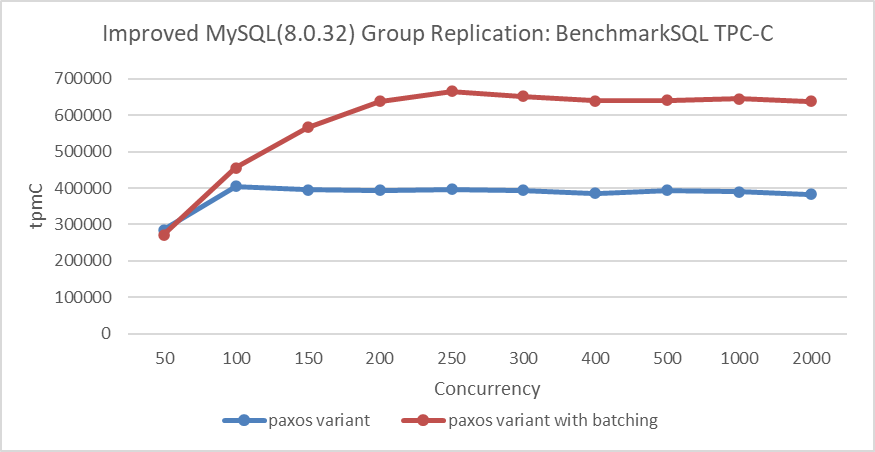

To achieve high throughput with either Mencius or Multi-Paxos, leveraging batching and pipelining technologies is essential. These optimizations, commonly used in state machine replication [49], significantly enhance performance. For instance, the figure below illustrates how batching improves Group Replication throughput in local area network scenarios.

Figure 4-14. Effect of batching on Paxos algorithm performance in LAN environments.