The-Art-of-Problem-Solving-in-Software-Engineering_How-to-Make-MySQL-Better

Chapter 1: Traditional Methods for Solving MySQL Problems

1.1 Current State of Solving MySQL Problems

Solving problems related to MySQL usage is generally straightforward and involves gathering information and applying logical reasoning, making these problems typically resolvable. However, tackling inherent problems within MySQL itself proves significantly more complex. Fortunately, MySQL users are resourceful and have devised various solutions, such as implementing thread pools to mitigate scalability challenges.

To effectively solve the myriad problems of MySQL, relying solely on peripheral fixes and patches is inadequate. It’s essential to delve into the core nature of these problems and comprehensively address them to achieve meaningful progress. For example, MySQL Group Replication has persistently struggled with instability. Despite robust development efforts, the ongoing challenge lies in adopting the correct problem-solving approach, resulting in difficulties in reducing bugs.

1.2 How Are MySQL Problems Solved?

Here are some classic problems listed, along with typical resolutions in real-world MySQL usage scenarios.

1.2.1 Addressing Scalability Problems in MySQL 5.7

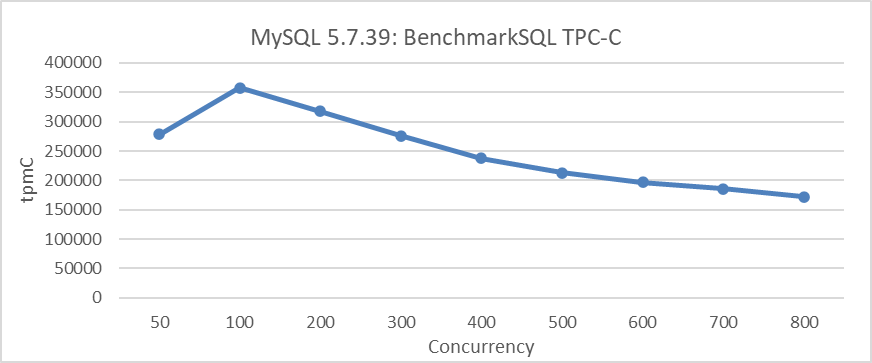

The following figure illustrates the relationship between TPC-C throughput and concurrency in MySQL 5.7.39 under a specific configuration. This includes setting the transaction isolation level to Read Committed and adjusting the innodb_spin_wait_delay parameter to mitigate throughput degradation.

Figure 1-1. Scalability problems in MySQL 5.7.39 during BenchmarkSQL testing.

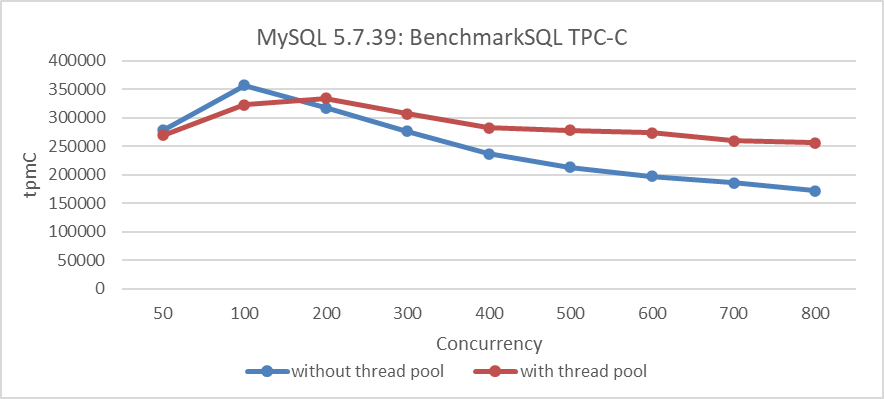

From the figure, it is evident that scalability problems significantly limit the increase in MySQL throughput. For example, after 100 concurrency, the throughput begins to decline. Due to MySQL’s historical scalability challenges, Percona even open-sourced a thread pool to address these problems. The following figure illustrates the relationship between TPC-C throughput and concurrency after configuring the Percona thread pool.

Figure 1-2. Percona thread pool mitigates scalability problems in MySQL 5.7.39.

For MySQL 5.7.39, the thread pool effectively mitigates the decline in throughput degradation, although it also slightly reduces peak throughput due to inherent overhead costs. This overhead becomes more noticeable when comparing performance at lower concurrency levels.

As MySQL 8.0 versions improve scalability, the effectiveness of the thread pool in mitigating throughput degradation diminishes. Subsequent chapters will provide real-world cases to substantiate this observation.

1.2.2 Enhancing Join Performance in MySQL

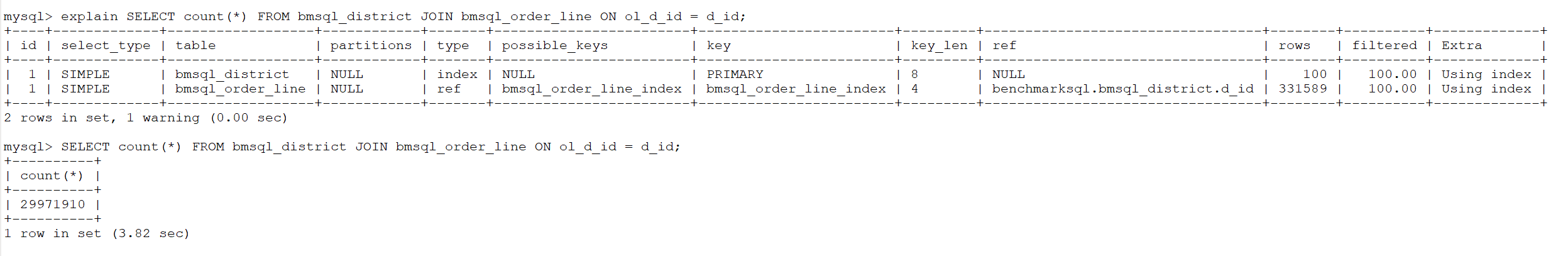

Due to the absence of hash join support in MySQL 5.7, the following statistical SQL query took 3.82 seconds to execute.

Figure 1-3. Non-hash join performance in MySQL 5.7.

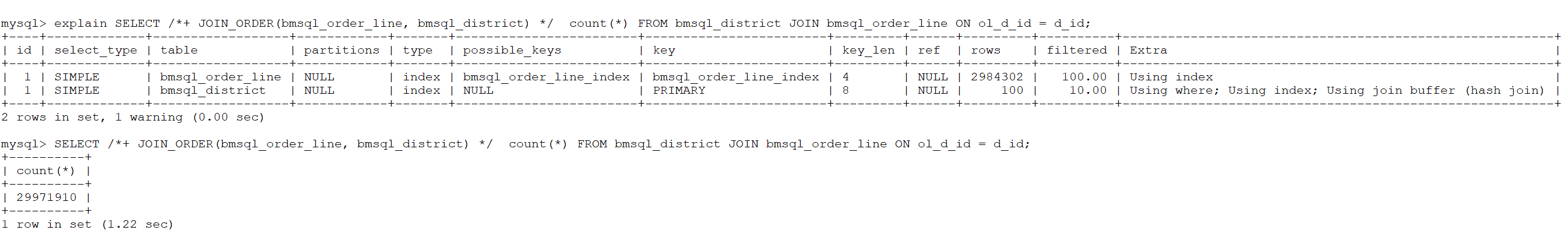

In MySQL 8.0, the introduction of hash joins in the execution plan has improved join performance. For the same SQL query mentioned earlier, specifying hash join through comments reduced the execution time to just 1.22 seconds, a significant improvement from the previously observed 3.82 seconds.

Figure 1-4. Hash join performance in MySQL 8.0.

This illustrates the improvement in join execution introduced in MySQL 8.0, highlighting one of its key advancements.

1.2.3 Challenges of MySQL Semisynchronous Replication in Large-Scale Deployments

Since the introduction of the Paxos protocol, an increasing number of databases have adopted state machine replication to construct a highly available cluster.

The Paxos protocol relies on a majority-based mechanism rooted in set theory to achieve consensus. For instance, in a cluster with 3 MySQL nodes, 2 nodes can form a majority. If these 2 nodes reach consensus, the system can operate continuously. Theoretically, adherence to this majority-based mechanism should prevent divergence or split-brain problems under any anomaly.

Raft, another widely used protocol, is essentially a simplified version of the Paxos protocol. The following section describes Meta’s implementation of MySQL high availability using the Raft protocol [38], which simplifies traditional high availability processes.

Figure 1-5. Reasons Meta uses raft.

Meta’s case study demonstrates that the new solution based on the Raft protocol simplifies high availability challenges. Raft is often viewed as a streamlined version of the Paxos protocol. Similarly, a Group Replication solution based on the Paxos protocol, if implemented correctly, could also offer an elegant solution.

1.2.4 Majority-Based Mechanism Performance and Its Accuracy

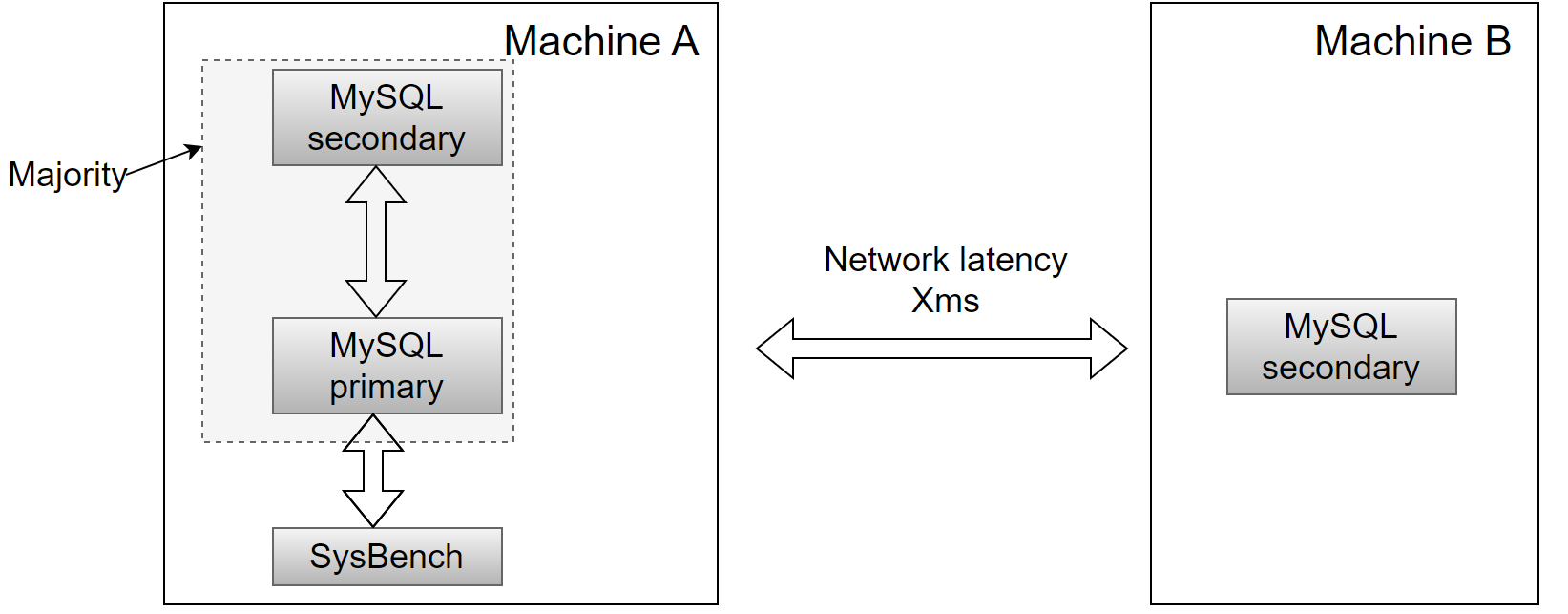

With the transaction isolation level set to Read Committed, simulations based on Group Replication were conducted under various network latency conditions.

The deployment setup of Group Replication is illustrated as follows: On machine A, two MySQL instances are deployed—one serving as the primary and the other as the secondary. These two instances form the majority and communicate via localhost. Machine B hosts a third instance deployed as a member of the cluster, with a network latency of X milliseconds.

Figure 1-6. Deployment diagram for majority-based mechanism performance testing.

In theory, with a majority-based mechanism, a cluster of 3 nodes only needs responses from 2 nodes to provide results to the client. By this logic, local SysBench tests should demonstrate very high efficiency.

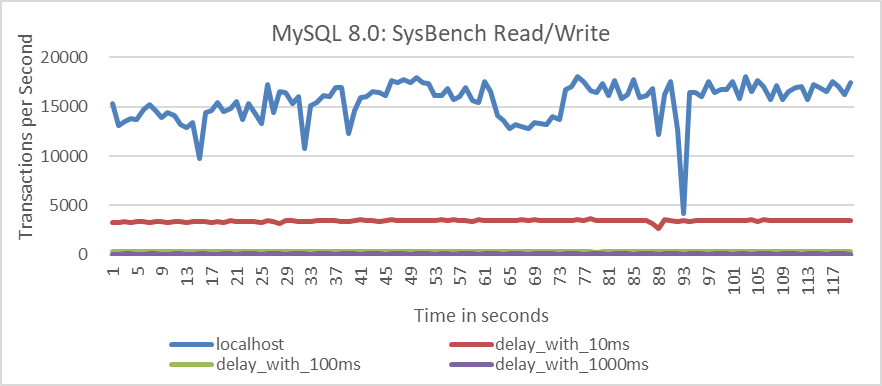

Throughput comparisons over time have been conducted for machine B in scenarios within the same data center and across data centers with latencies of 10ms, 100ms, and 1000ms. Specific results are illustrated in the following figure.

Figure 1-7. Performance testing results of the default multi-leader Paxos algorithm.

From the figure, it is evident that under the default mode of Group Replication, throughput across data centers deviates significantly from theoretical expectations. For example, in scenarios with 10ms network latency, the cluster’s throughput decreases to one-fifth of its original level. To address this discrepancy, starting with MySQL 8.0.27, the group_replication_paxos_single_leader option was introduced. Enabling this option utilizes the single leader Paxos algorithm instead of the default multi-leader Paxos algorithm.

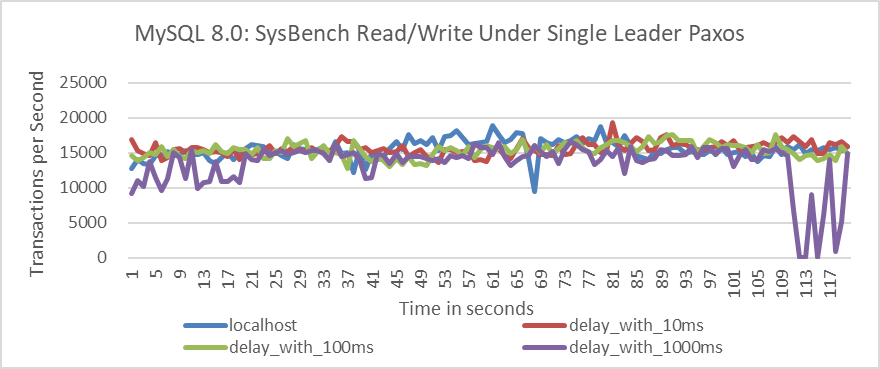

After configuring Group Replication to use the single leader Paxos algorithm, tests were conducted under the same conditions using the SysBench testing tool. The test results are as follows.

Figure 1-8. Performance testing results of the single-leader Paxos algorithm.

From the figure, it is evident that the results of the single leader mode are significantly better than previous results. However, the drawback is that the single leader mode can only function in MySQL’s single-primary mode, and its application scope is limited, unable to be applied in scenarios requiring strong consistency for read and write operations.

Is this modification to the underlying Paxos algorithm truly the optimal solution? This will be explored in depth in the following chapters.

1.2.5 Group Replication: Localhost Deployment Reports Unreachable

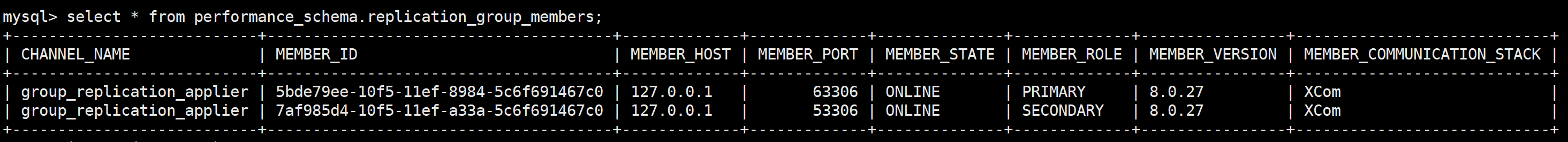

Deploying Group Replication with two nodes on the same machine, where communication between these nodes occurs via localhost, theoretically should not encounter network-related jitter, packet loss, or problems with unreachable peers under normal conditions.

Figure 1-9. Localhost deployment relationships displayed by Performance Schema.

During TPC-C data loading tests with BenchmarkSQL under normal pressure, the MySQL error logs revealed multiple instances of the primary and secondary nodes reporting each other as unreachable.

Here is a partial screenshot of the error log from the MySQL primary:

Figure 1-10. A partial screenshot of the error log from the MySQL primary.

Here is a partial screenshot of the error log from the MySQL secondary:

Figure 1-11. A partial screenshot of the error log from the MySQL secondary.

From these logs, warnings indicating ‘has become unreachable’ are evident. Under normal conditions, frequent ‘unreachable’ reports in a localhost scenario like this are unexpected. Blaming the network for Group Replication’s delayed problem handling isn’t optimal. Future chapters will explore enhancements to the network probing mechanism to address these false reporting problems.

1.3 Summary

This chapter analyzed how users approach solving MySQL problems. MySQL 8.0 has made strides in improvement, notably in mitigating scalability problems and introducing support for hash joins, which is a positive development. However, there remain numerous unsolved problems, both longstanding and newly emerging. Effectively addressing MySQL problems demands a thorough understanding of the problems and relevant theories; otherwise, the understanding may be incomplete.

The next chapter will demonstrate the considerable challenge of solving obscure MySQL problems through various case studies. It necessitates a broad knowledge base and extensive logical reasoning to pinpoint the root causes of these problems.