The-Art-of-Problem-Solving-in-Software-Engineering_How-to-Make-MySQL-Better

Chapter 2: Mysterious MySQL Problems

MySQL, the most popular open-source database software with a history spanning several decades, is renowned for its simplicity and user-friendly nature, making it a cornerstone choice among internet companies. Despite its widespread adoption, MySQL faces a variety of challenges.

This chapter introduces nine puzzling MySQL problems or phenomena that serve as examples and lay the groundwork for deeper exploration in subsequent topics.

2.1 SysBench Read-Write Test Demonstrates Super-Linear Throughput Growth

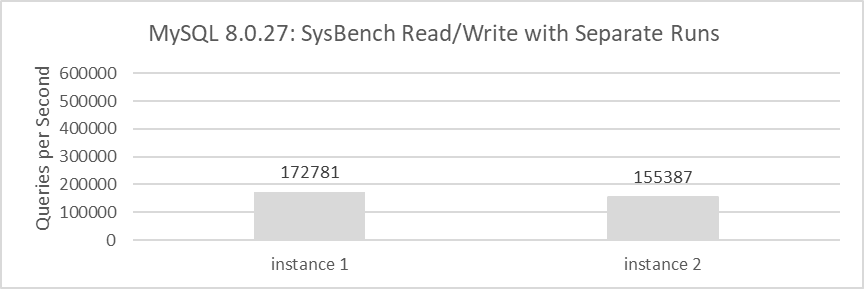

In the MySQL 8.0.27 release version, for example, in a 4-way NUMA environment on x86 architecture, using SysBench to remotely test MySQL’s read-write capabilities. The MySQL transaction isolation level is set to Read Committed. MySQL instances 1 and 2 are deployed on the same machine, with a testing duration of 60 seconds. The results of separate SysBench tests for MySQL instance 1 and instance 2 are shown in the following figure.

Figure 2-1. Throughput of MySQL running separately.

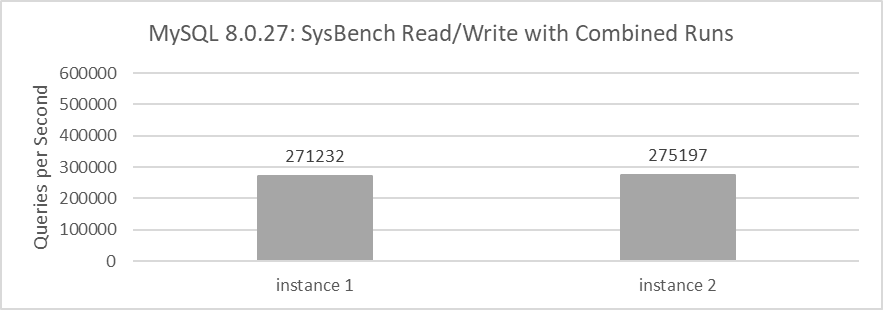

The throughput of each instance is modest, with figures of 172,781 QPS and 155,387 QPS respectively. When combined, the two instances achieve a total throughput of 328,168 QPS. When using SysBench to simultaneously test the read and write capabilities of these two instances, the obtained throughputs are 271,232 QPS and 275,197 QPS respectively.

Figure 2-2. Throughput of MySQL running together.

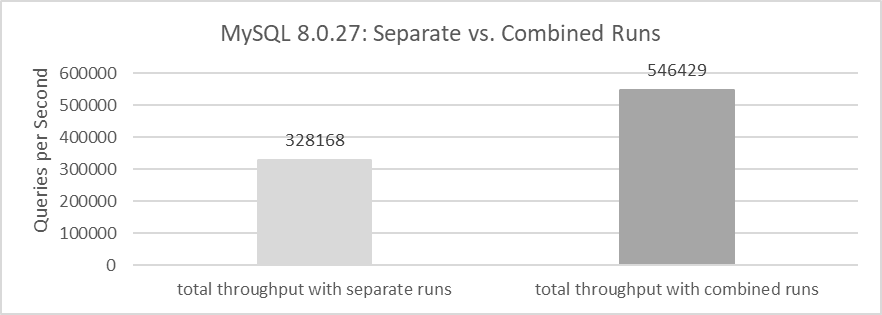

The combined throughput of the two MySQL instances is 546,429 QPS. This data demonstrates that when these two MySQL instances share the same machine, the combined throughput is significantly higher than the sum of their individual throughputs when run separately. For detailed statistical comparisons, please refer to the following figure.

Figure 2-3. Total throughput of running separately vs. running together.

In terms of mathematical logic, if the total throughput when running two instances together is roughly equal to the sum of the throughputs when running them separately, it represents a linear relationship. If the combined throughput exceeds this sum, it suggests a super-linear relationship.

What drives super-linear relationships? Does MySQL exhibit super-linear behavior? Understanding this requires a deep dive into computer fundamentals and advanced MySQL concepts.

2.2 Unexpected Decline in TPC-C Throughput After Applying PGO

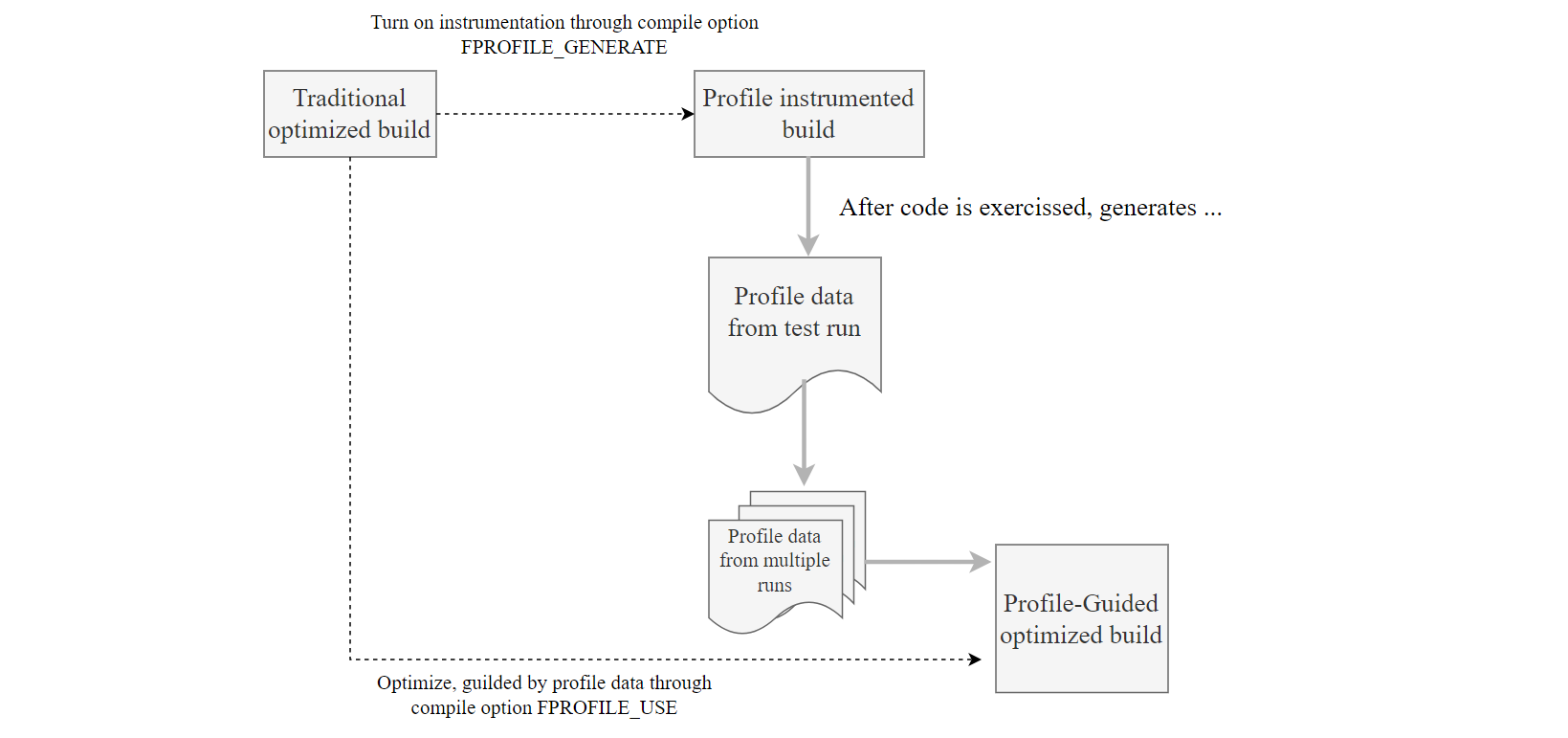

Profile-guided optimization (PGO) is a well-established technique for improving compile-time optimization decisions. Profile information is collected through instrumentation or sampling of the executable, and this data is used to optimize the executables it was gathered from [45]. Despite its effectiveness, PGO has not been widely adopted by software projects due to its cumbersome dual-compilation model. Nevertheless, PGO remains a highly valuable optimization technique to consider for improving MySQL performance, as it theoretically has the potential to significantly improve MySQL’s efficiency.

The following diagram illustrates the application of PGO to higher versions of MySQL 8.0.

Figure 2-4. Using PGO in higher versions of MySQL 8.0: a step-by-step guide.

From the diagram, the Profile-Guided Optimization (PGO) mechanism involves several steps:

- Initially, compile a specific version of MySQL with the compilation option “-DFPROFILE_GENERATE=ON”.

- Start this MySQL version and capture training data by running performance tests such as TPC-C, which helps collect performance metrics.

- After completing the training phase, perform a second compilation with the option “-DFPROFILE_USE=ON”. During this compilation, the compiler automatically utilizes the gathered statistical data to optimize conditional branches and related aspects, significantly improving the performance of the resulting MySQL executable.

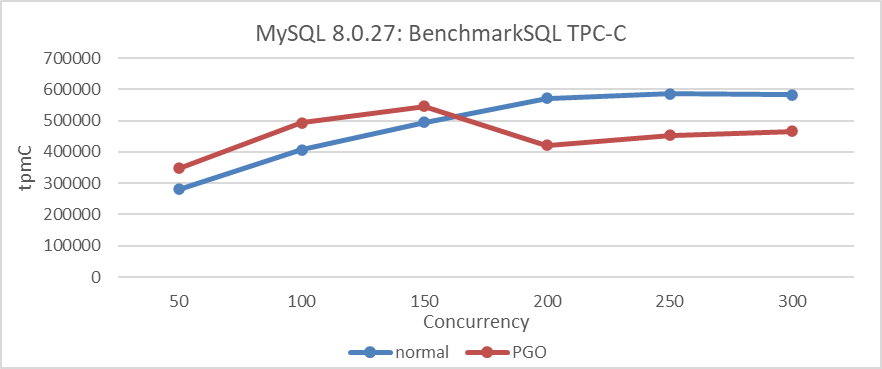

The following figure illustrates the relationship between throughput and concurrency before and after applying PGO to MySQL 8.0.27.

Figure 2-5. Performance comparison tests before and after using PGO in MySQL 8.0.27.

Based on the figure, it’s evident that PGO leads to notable improvements in MySQL throughput at lower concurrency levels. However, beyond 150 concurrency, both the overall throughput and peak performance show a decline.

Does PGO primarily benefit low-concurrency scenarios, or are there additional factors limiting its effectiveness? This question delves into queueing theory and system architecture. Further exploration of practical computer fundamentals will provide deeper insights into this matter.

2.3 Adverse Effects of Thread Pool on MySQL After Scalability Enhancements

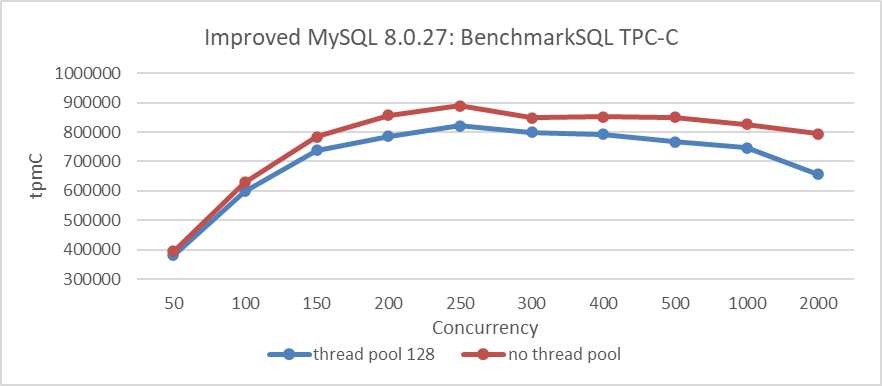

After applying various scalability patches to MySQL 8.0.27, it’s crucial to evaluate whether the Percona thread pool still effectively addresses scalability problems. The following figure depicts the results of TPC-C testing on a standalone MySQL instance using BenchmarkSQL. The deep blue line indicates the configuration with the Percona thread pool enabled (thread pool size = 128), while the deep red line represents the configuration with the thread pool disabled. The test covered concurrency levels ranging from 50 to 2000, utilizing a database with 1000 warehouses.

Figure 2-6. Enabling the Percona thread pool resulted in a significant reduction in throughput compared to when it was disabled.

From the figure, it is clear that enabling the Percona thread pool clearly led to a significant decrease in throughput compared to having it disabled. Notably, even without the thread pool enabled, MySQL 8.0 showed a marked improvement in scalability compared to MySQL 5.7. This suggests that the additional benefit of using the Percona thread pool for improving TPC-C testing was limited. Moreover, the Percona thread pool mechanism itself introduces overhead, which is reflected in the figure’s results.

It’s important to acknowledge that the Percona thread pool remains valuable in scenarios involving frequent connection creation and severe contention. However, the key question remains: what exactly contributed to such significant improvements in MySQL scalability? Future chapters will explore these mysteries further.

2.4 In MySQL 8.0, TPC-C Throughput Drops Too Quickly

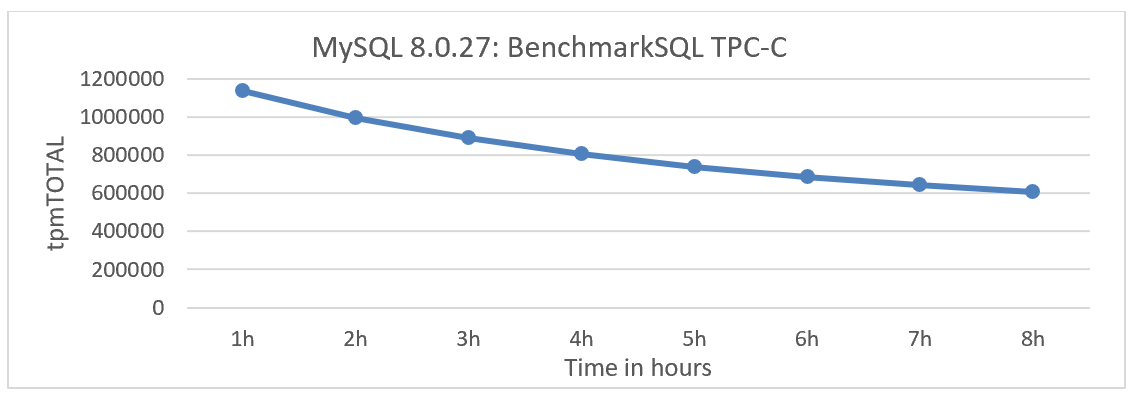

The standards for long-term TPC-C testing are as follows: the TPC-C benchmark requires that the database run for at least eight hours with jitters less than 2% in two hours [14].

Based on MySQL 8.0.27, long-term TPC-C testing was conducted using the BenchmarkSQL tool. Below are the BenchmarkSQL testing parameters:

warehouses=1000

loadWorkers=100

terminals=200

warehouses-begin=1

warehouses-end=1000

//To run specified transactions per terminal- runMins must equal zero

runTxnsPerTerminal=0

//To run for specified minutes- runTxnsPerTerminal must equal zero

runMins=480

//Number of total transactions per minute

limitTxnsPerMin=0

//Set to true to run in 4.x compatible mode. Set to false to use the

//entire configured database evenly.

terminalWarehouseFixed=false

//The following five values must add up to 100

//The default percentages of 45, 43, 4, 4 & 4 match the TPC-C spec

newOrderWeight=45

paymentWeight=43

orderStatusWeight=4

deliveryWeight=4

stockLevelWeight=4

From the above, it can be seen that there are 1000 warehouses, with a concurrency of 200, and terminalWarehouseFixed is set to false. This setting enables each transaction to use a different warehouse ID every time, thereby accessing data across all warehouses.

The following figure illustrates the throughput over time during long-term testing. The TPC-C throughput shows a decline rate that significantly surpasses expectations, nearing a 50% decrease.

Figure 2-7. Performance degradation exposed during BenchmarkSQL testing of MySQL 8.0.27.

This problem was identified during testing using BenchmarkSQL and may not necessarily occur with other TPC-C testing tools. As of the current version, MySQL 8.0.40, the problem of rapid throughput decline has not been fully solved. Subsequent chapters will delve into detailed explanations of the underlying causes of this problem.

2.5 Repeatable Read Surprisingly Outperforms Read Committed

Transaction isolation is fundamental to database processing, represented by the ‘I’ in the ACID acronym. The isolation level determines the balance between performance and the reliability, consistency, and predictability of results when multiple transactions concurrently make changes and queries. Commonly used isolation levels are Read Committed, Repeatable Read, and Serializable. By default, InnoDB uses Repeatable Read.

InnoDB employs distinct locking strategies for each isolation level, impacting query locking behavior under concurrent conditions. Depending on the isolation level, queries may need to wait for locks currently held by other sessions before execution begins [13]. There’s a common perception that stricter isolation levels can degrade performance. How does MySQL perform in practical scenarios?

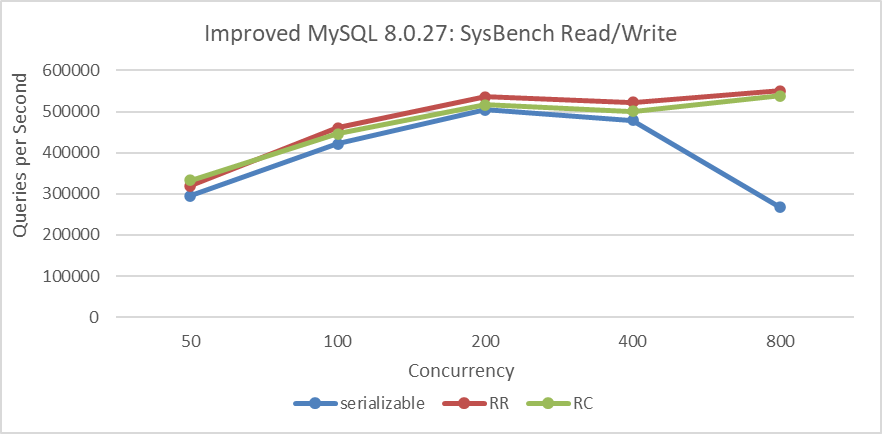

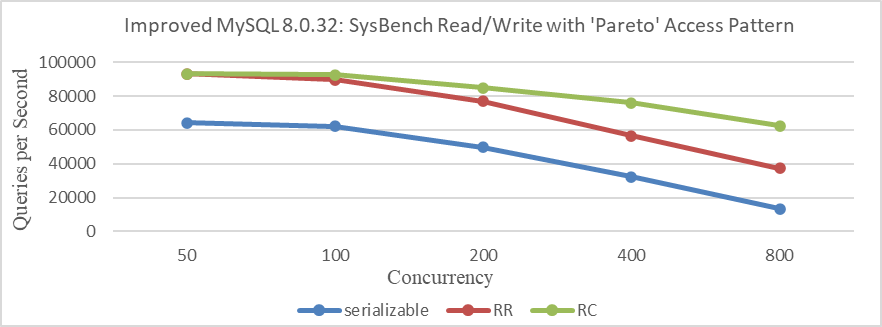

Tests were conducted across Serializable, Repeatable Read (RR), and Read Committed (RC) isolation levels using two benchmark types: SysBench uniform and pareto tests. The SysBench uniform test simulates low-conflict scenarios, while the SysBench pareto test models high-conflict situations. Due to excessive deadlock logs generated during the SysBench pareto test, which significantly interfered with performance analysis, these logs were suppressed by modifying the source code to ensure fair testing conditions. Moreover, the MySQL testing program utilized a modified version for accuracy, rather than the original version.

The figure below presents results from the SysBench uniform test, where concurrency increases from 50 to 800 in doubling increments. Given the few conflicts in this test type, there is little variation in throughput among the three transaction isolation levels at low concurrency levels. However, beyond 400 concurrency, the throughput of the Serializable isolation level exhibits a notable decline.

Figure 2-8. SysBench read-write performance comparison with low conflicts under different isolation levels.

Below 400 concurrency, the differences are minor because of fewer conflicts in the uniform test. With fewer conflicts, the impact of lock strategies under different transaction isolation levels is reduced. However, Read Committed is mainly constrained by frequent acquisition of MVCC ReadView, resulting in performance inferior to Repeatable Read.

Continuing with the SysBench test under pareto distribution conditions, specific comparative test results can be seen in the following figure.

Figure 2-9. SysBench read-write performance comparison with high conflicts under different isolation levels.

The figure clearly illustrates that in scenarios with significant conflicts, performance differences due to lock strategies under different transaction isolation levels are pronounced. As anticipated, higher transaction isolation levels generally exhibit lower throughput, particularly under severe conflict conditions.

In scenarios with few conflicts, performance is primarily constrained by the overhead of acquiring ReadView in MVCC. This is because, under the Read Committed isolation level, MySQL must copy the entire active transaction list each time it reads from the global active transaction list, whereas under Repeatable Read, it only needs to obtain a copy of the active transaction list at the start of the transaction.

In summary, in low-conflict tests like SysBench uniform, the overhead of MVCC ReadView is the predominant bottleneck, outweighing lock overhead. Consequently, Repeatable Read performs better than Read Committed. Conversely, in high-conflict tests like SysBench pareto, lock overhead becomes the primary bottleneck, resulting in Read Committed outperforming Repeatable Read.

2.6 Group Replication Throughput Lower Than Semisynchronous Replication

During Group Replication operation, a certification database is maintained. Regular cleanup of outdated certification information is crucial to manage memory usage efficiently. However, this cleanup process involves acquiring a global latch, temporarily pausing MySQL primary execution until the certification information is cleared.

In contrast, traditional semisynchronous replication requires the MySQL secondary to process a substantial amount of relay log event information. Only after these relay log events are written to disk can the secondary send acknowledgment (ack) information back to the MySQL primary. This process includes network interactions, handling numerous relay log events, and disk flushes, resulting in relatively longer response times for semisynchronous replication.

Overall, with semisynchronous replication, the MySQL primary must wait for acknowledgment from the MySQL secondary after relay log events are written to disk before it can proceed. In contrast, Group Replication continues processing once consensus is achieved at the Paxos layer, without waiting for log writes at that layer. Theoretically, Group Replication can achieve higher throughput.

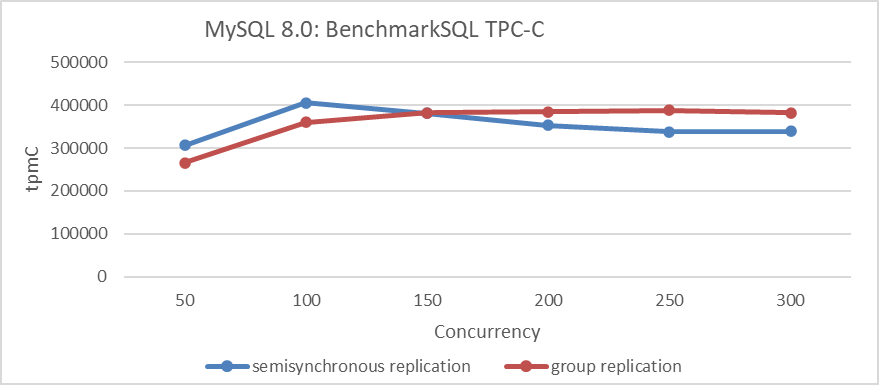

In the scenario of a two-node cluster, TPC-C throughput comparisons based on concurrency were conducted between Group Replication and semisynchronous replication. Please refer to the following figure for details.

Figure 2-10. Performance comparison between Group Replication and semisynchronous replication.

The figure indicates that under low concurrency, semisynchronous replication outperforms Group Replication, whereas Group Replication shows superior performance under high concurrency. Semisynchronous replication reaches its peak performance at 100 concurrency, whereas Group Replication peaks at 250 concurrency but offers lower peak performance than semisynchronous replication. These test results are unexpected. What could be the problem?

The root problem lies in the certification database mechanism used by Group Replication, which is absent in semisynchronous replication. This mechanism involves substantial memory allocation and deallocation, significantly limiting throughput improvement. Despite not requiring Paxos log persistence, this bottleneck negates the advantages of Group Replication. It is clear that the implementation of the certification database mechanism poses the primary performance challenge for Group Replication.

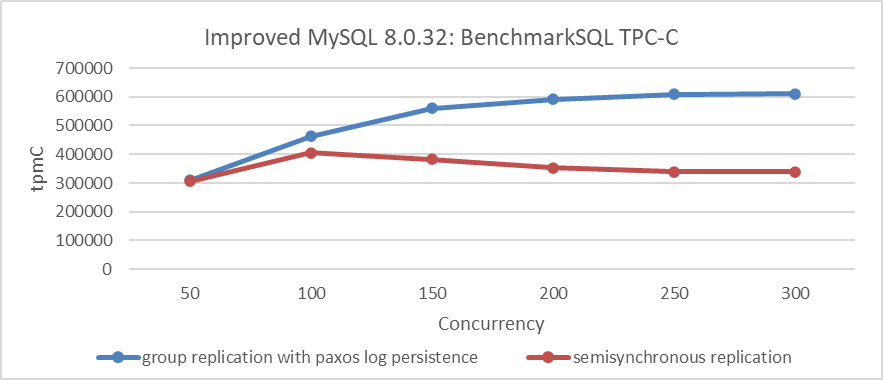

2.7 Modified Group Replication Outperforms Semisynchronous Replication

Group Replication has been extensively enhanced while addressing scalability problems in MySQL 8.0.32. To validate these improvements, simultaneous testing of semisynchronous replication and Group Replication with Paxos log persistence was conducted. The deployment setup included two-node configurations for both semisynchronous and Group Replication, hosted on the same machine with independent NVMe SSDs and NUMA binding to isolate each node. Specifically, the MySQL primary utilized NUMA nodes 0 to 2, while the MySQL secondary utilized NUMA node 3. All settings, except those directly related to semisynchronous or Group Replication configurations, remained identical.

The following figure shows the throughput comparison of semisynchronous replication and Group Replication with Paxos log persistence under different concurrency levels.

Figure 2-11. Performance comparison between Group Replication with Paxos log persistence and semisynchronous replication.

Both employ persistence mechanisms, with Group Replication utilizing Paxos log persistence and semisynchronous replication utilizing relay log persistence. Due to these distinct mechanisms, Group Replication with Paxos log persistence demonstrates significantly superior performance compared to semisynchronous replication.

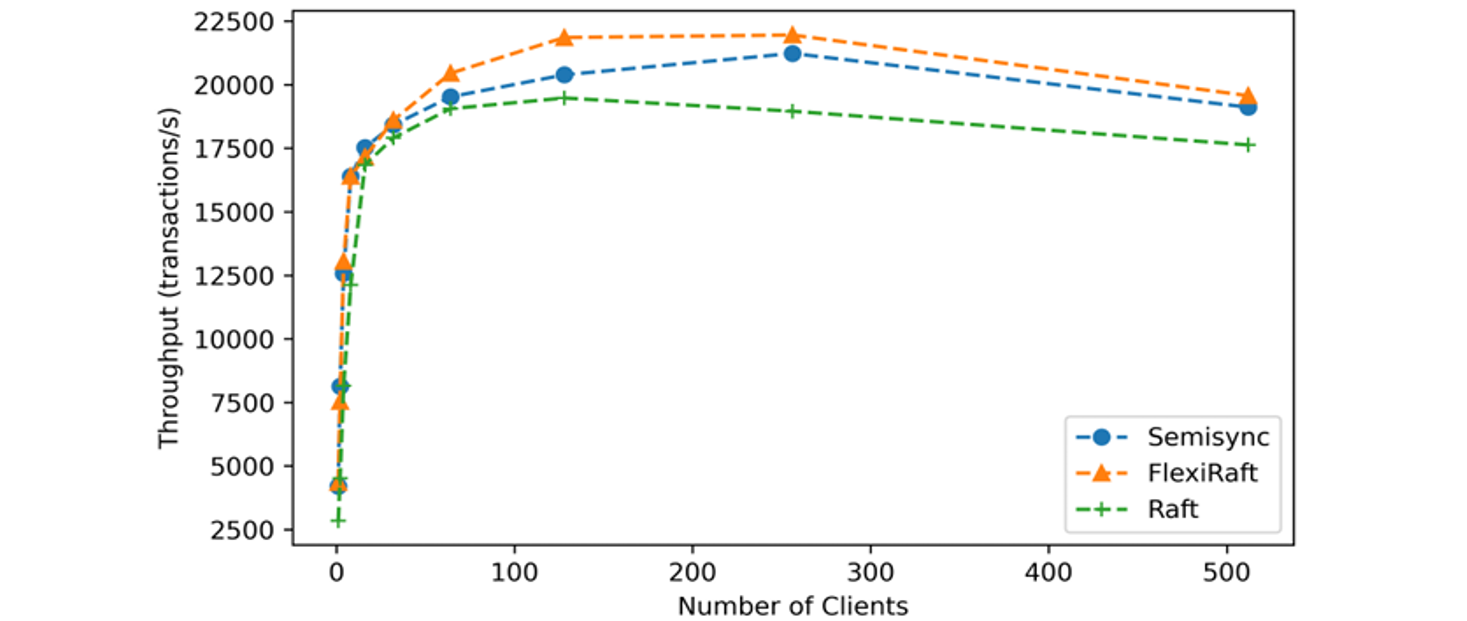

Meta Company has implemented a MySQL high availability solution based on Raft. According to tests conducted by Meta Company developers, the performance of the Raft-based improved version is comparable to that of semisynchronous replication. For specific details, refer to the figure below [42].

Figure 2-12. Throughput comparison borrowed from Meta paper.

In theory, Group Replication can leverage a batching-based disk persistence mechanism, eliminating the need to process binlog events during disk writes, thereby achieving higher expected throughput. Future chapters will delve into detailed discussions on modifying Group Replication and examining specific factors contributing to the scalability challenges of native semisynchronous replication.

2.8 SysBench Shows No Effect, TPC-C Performs Well

The specifics of the lock-sys optimization in MySQL 8.0 are detailed below:

commit 1d259b87a63defa814e19a7534380cb43ee23c48

Author: Jakub Łopuszański <jakub.lopuszanski@oracle.com>

Date: Wed Feb 5 14:12:22 2020 +0100

WL#10314 - InnoDB: Lock-sys optimization: sharded lock_sys mutex

The Lock-sys orchestrates access to tables and rows. Each table, and each row,

can be thought of as a resource, and a transaction may request access right for

a resource. As two transactions operating on a single resource can lead to

problems if the two operations conflict with each other, Lock-sys remembers

lists of already GRANTED lock requests and checks new requests for conflicts in

which case they have to start WAITING for their turn.

Lock-sys stores both GRANTED and WAITING lock requests in lists known as queues.

To allow concurrent operations on these queues, we need a mechanism to latch

these queues in safe and quick fashion.

In the past a single latch protected access to all of these queues.

This scaled poorly, and the management of queues become a bottleneck.

In this WL, we introduce a more granular approach to latching.

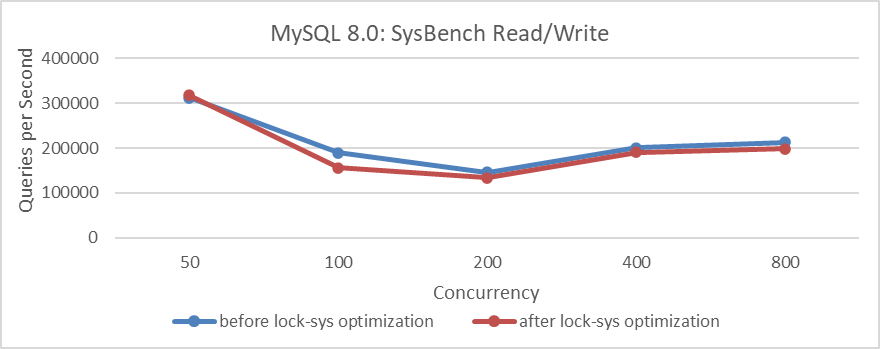

This represents a scalability improvement in MySQL 8.0 by addressing the global latch bottleneck and optimizing lock scheduling in InnoDB. To validate the effectiveness of this lock-sys optimization, refer to the specific test results illustrated in the figure below using SysBench read-write tests.

Figure 2-13. Comparison of SysBench read-write tests before and after lock-sys optimization.

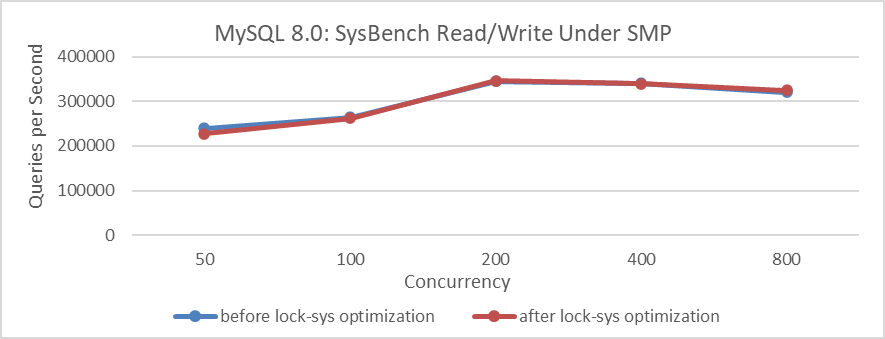

It’s surprising that after implementing the lock-sys optimization, the throughput decreased, which was unexpected. To mitigate interference from NUMA compatibility problems in MySQL code, the MySQL running instance was bound to NUMA node 0 (similar to an SMP environment). The test results are as follows.

Figure 2-14. Comparison of SysBench read-write tests before and after lock-sys optimization under SMP.

The figure shows that the difference before and after optimization is minimal, almost negligible. This suggests that during the testing process, the effectiveness of the lock-sys optimization is overshadowed by other factors, resulting in distorted test results. However, binding to NUMA node 0 reduced interference from other bottlenecks, narrowing the performance gap. It also indicates that the lock-sys optimization has limited impact on SysBench standard read-write tests.

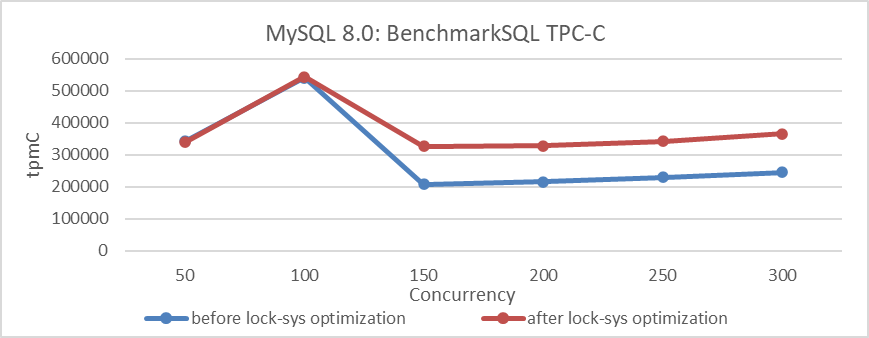

Using BenchmarkSQL for TPC-C testing, the results are as follows:

Figure 2-15. Comparison of BenchmarkSQL tests before and after lock-sys optimization.

The figure demonstrates a noticeable improvement from the lock-sys optimization. However, it raises questions as to why SysBench testing shows no effect while BenchmarkSQL testing does. Understanding the differences between these two tools and important considerations during testing will be thoroughly discussed in upcoming chapters.

2.9 Is Disabling NUMA Really Beneficial for MySQL?

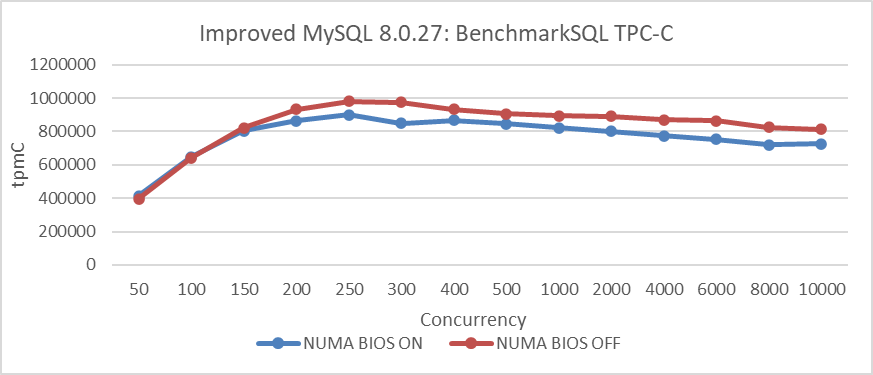

The impact of disabling NUMA on the MySQL primary was initially tested. The deployment setup was as follows: BenchmarkSQL high-pressure stress tests were conducted on two x86 machines with identical hardware configurations. One machine had NUMA disabled in the BIOS, while the other had NUMA enabled. The comparison of TPC-C throughput versus concurrency is illustrated in the figure below.

Figure 2-16. Significantly improved TPC-C throughput by disabling NUMA in the BIOS.

The figure demonstrates that disabling NUMA on x86 machines significantly improves TPC-C throughput. This improvement stems from the favorable memory allocation mechanism after disabling NUMA in the BIOS, particularly beneficial for applications like MySQL primary servers.

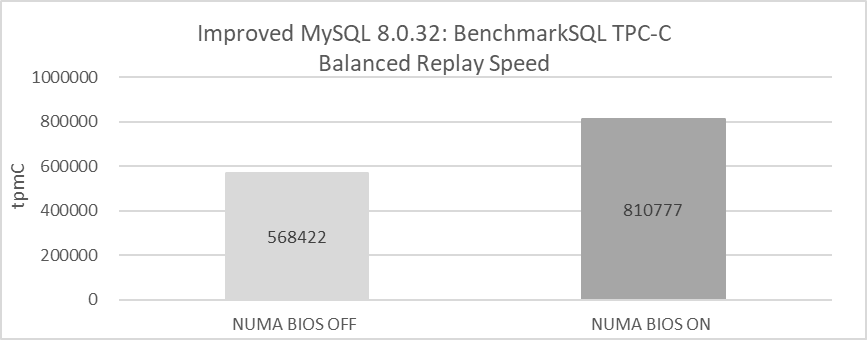

Now, does disabling NUMA also benefit MySQL secondary replay? Using the same machines mentioned earlier for testing, the setup details are as follows: in the environment where NUMA is disabled in the BIOS, NUMA binding cannot be utilized, allowing all memory to be utilized. Conversely, in the environment where NUMA is enabled in the BIOS, MySQL secondaries are bound to NUMA node 0. The following figure illustrates the balanced replay speeds tested in these different environments.

Figure 2-17. Comparison of balanced replay speed before and after disabling NUMA in the BIOS.

The figure reveals that disabling NUMA at the BIOS level results in a balanced replay speed of only around 570,000 tpmC, primarily due to the unsolved NUMA unfriendliness problems with MySQL secondaries. In contrast, enabling NUMA and binding MySQL secondaries to a single NUMA node can achieve a balanced replay speed exceeding 810,000 tpmC. This test highlights the disadvantage of disabling NUMA at the BIOS level for MySQL secondary replay efficiency. Effective MySQL secondary replay with NUMA disabled necessitates addressing these NUMA unfriendliness problems, as failure to do so significantly reduces efficiency. The upcoming Chapter 10 on improving MySQL secondary replay will provide a detailed examination of these NUMA unfriendliness problems.

2.10 Summary

This chapter delves into classic and intricate MySQL problems, which pose significant challenges for analysis. The resolution of these problems begins with a detailed logical analysis, as outlined in the following chapter. Addressing and solving these problems necessitates a profound understanding of computer fundamentals and MySQL internals. Computer fundamentals encompass a broad range of topics including computer architecture, data structures, algorithms, operating systems, computer networks, compilers, queueing theory, and distributed systems theory, among others. These topics will be thoroughly explored in Chapter 4. Chapter 5 will focus specifically on MySQL internals.